Glimpses of the Incarcerated: Enslaved People in San Juan’s Real Cárcel

Daniel Alejandro Ramos Matos

Ph.D. Student in History, Lehigh University

PRAC Graduate Summer Intern 2025

As she walked through the streets of Río Piedras on September 8, 1860, Francisca was arrested by orders of the town’s mayor, Tomístocles Andino. This was not her first encounter with local authorities. Since mid-August, Andino had maintained a constant line of communication with San Juan’s corregidor (local magistrate), reporting Francisca’s unlawful and frequent visits to Río Piedras, and according to Andino, Francisca, enslaved by San Juan resident Belén Prieto, lacked a passport authorizing her to travel between municipalities. He also disapproved of her “detrimental” concubinage with Pascual Benítez, a resident of Río Piedras. On August 27, Andino intercepted and sent Francisca to the magistrate, requesting Belén Prieto to punish her and ensure she never returned to Río Piedras. Otherwise, he warned, Francisca would be considered a fugitive and prosecuted accordingly. Francisca never complied with Andino’s orders and continued her visits to Río Piedras until her eventual arrest.

Andino’s supervision of Francisca’s whereabouts, his awareness of her personal relationships, and his communication with authorities in San Juan exemplify the state-led repressive mechanisms that defined Spanish colonial governance in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico. In the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), colonial authorities in Puerto Rico and Spain enacted measures to restrain the spread of revolutionary ideals, especially among the enslaved. The administrations of governors Toribio Montes (1804-1809) and Salvador Meléndez Bruna (1809-1820) were characterized by the criminalization of vagrancy and heightened surveillance of the daily movements of Puerto Rico’s inhabitants and foreigners who arrived through legal or illicit means.[1] Under Governor Miguel de la Torre (1822-1837), these practices were codified in the 1824 Bando de Policía y Buen Gobierno, which required municipal mayors to “inform authorities of any foreigners or strangers passing through their towns” and “to create daily logs of information about everything that happened in their municipality.” The bando also gave mayors the power to regulate who could access residents’ homes under their jurisdiction.[2] These measures contributed to the expansion of carceral practices and the criminalization of enslaved people. In his longue-durée history of Puerto Rico’s incarcerated population, Fernando Picó notes that the number of enslaved individuals imprisoned increased significantly in the 1820s, mainly due to their acts of resistance toward enslavement and the precarious conditions of sugar production.[3]

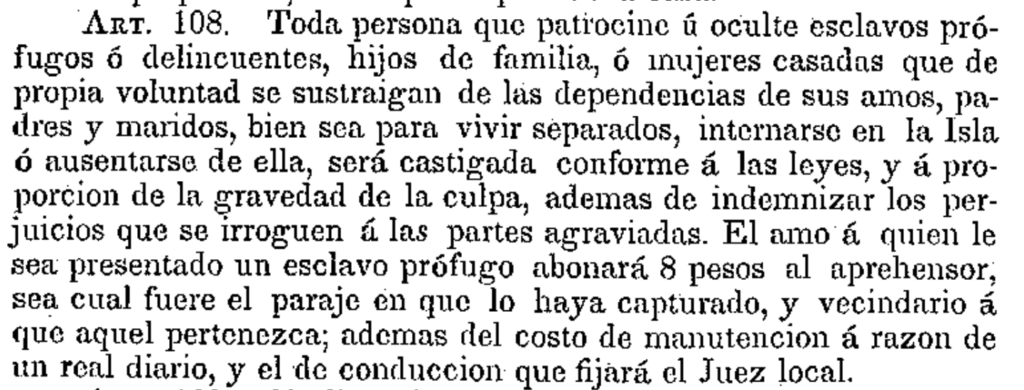

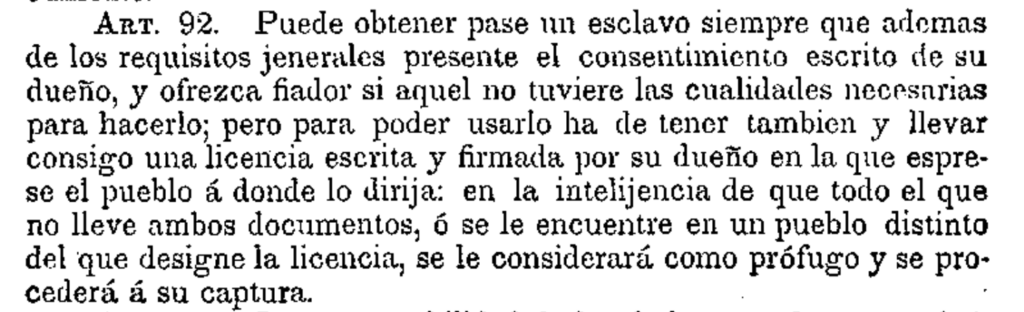

Francisca’s actions violated public order articles 92 and 108 within this legal framework. Article 92 (fig. 1) required enslaved individuals to carry a written consent or license signed by their slaveholders authorizing them to cross municipal jurisdiction and specifying their destination. Article 108 (fig. 2), among other stipulations, established penalties for anyone who harbored enslaved runaways, children, or married women who voluntarily fled from their slaveholders, fathers, and husbands. Slaveholders were required to cover the costs of capturing, maintaining, and transporting runaway slaves.

Fig. 1. Article 92 of the Bando de Policía y Buen Gobierno, Biblioteca Nacional de España

Fig. 2. Article 108 of the Bando de Policía y Buen Gobierno, Biblioteca Nacional de España

Francisca was likely transported from Río Piedras to San Juan’s Real Cárcel, where she awaited to be claimed by her slaveholder, Belén Prieto, becoming part of the hundreds of enslaved Africans and Afrodescendants imprisoned in Puerto Rico’s capital during the nineteenth century. Her story is preserved within the “Cárcel” series of the Fondo Municipal de San Juan at the Archivo General de Puerto Rico (AGPR), which I had the privilege of organizing as a PRAC Mellon Summer Intern alongside Ailish F. Quiñones Rivera.[4] Under the supervision of archivist Pedro Roig, Ailish and I were tasked with arranging the collection’s manuscripts in chronological order, assigning legajo and expediente numbers, and identifying documents regarding enslaved individuals to be placed in a separate box that became the “Esclavos” subseries. Overall, the collection comprises sources from the 1840s to the 1920s and includes records of inmate transfers and admissions to San Juan’s Real Cárcel, sentencing and confinement documents, jail releases, receipts for the payments of transfers and maintenance of inmates, criminal background reports, correspondence, and more.[5] Ailish and I organized the collection into the following legajos and expedientes:

- Legajo 186 (Years: 1842-1859), expedientes 1-8

- Legajo 187 (Years: 1859-1881), expedientes, 9-22

- Legajo 188 (Years: 1875-1898), expedientes, 23-34

- Legajo 189 (Years: 1897-1903), expedientes, 35-46

- Legajo 190 (Years: 1898-1899), expedientes, 47-51

- Legajo 191 (Years: 1903-1924), expedientes, 52-59

- Legajo 192 (Years: 1845-1867), expedientes 60-61

Legajo 192 constitutes the “Esclavos” subseries, containing all the documents we could locate that mention enslaved inmates. I wish to emphasize, however, that anyone interested in studying the experiences of enslaved individuals in San Juan’s correctional facilities should consult the collection as a whole, not only for the broader perspective it offers but also because there are likely many more relevant sources that escaped our sight. Indeed, we conducted multiple revisions of the collection, and with each pass, the number of folios in Legajo 192 grew more each time.

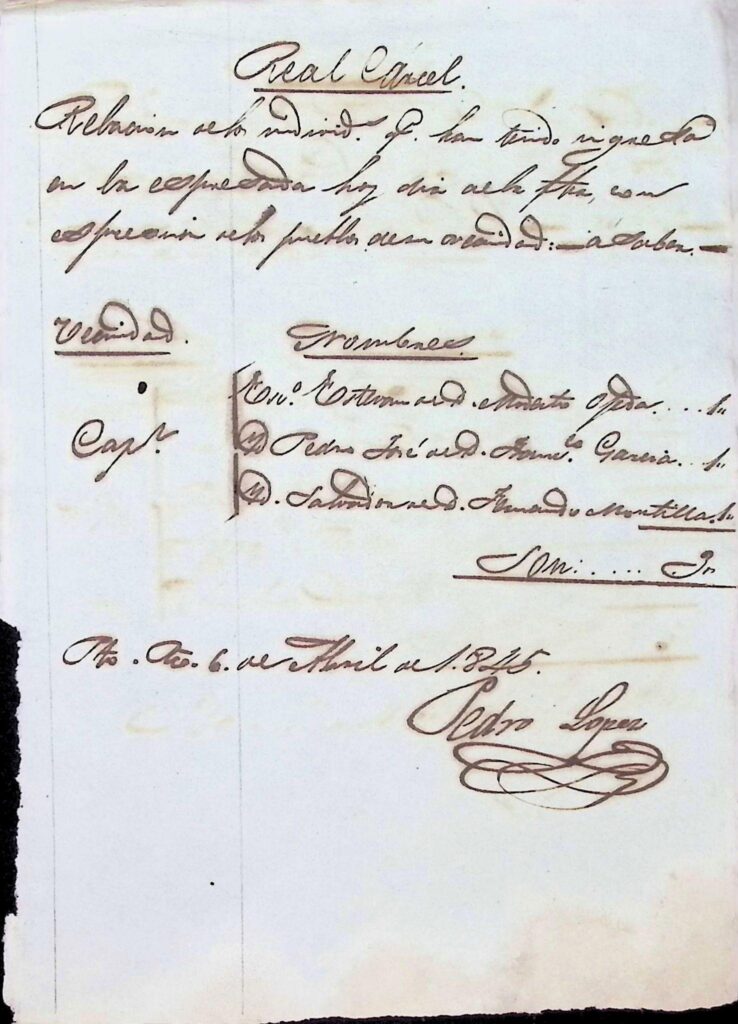

As I worked through this collection, I became increasingly struck by how frequently enslaved Africans and Afrodescendants were admitted to the Real Cárcel. Most sources identifying enslaved inmates are admission registers that record their entry to the jail. These include their names, place of origin, and the names of their slaveholders. For example, fig. 3 shows the admission of three enslaved individuals to the Real Cárcel on April 6, 1845. The column “Vecindad” (neighborhood) lists all three as residents of the “Capital” (San Juan). The first person, Esteban, is identified as “Esco.,” an abbreviation of esclavo (slave), while the other two, Pedro José and Salvador, are labeled “Id.,” indicating the same status. Their slaveholders were Modesto Ojeda, Francisco García, and Fernando Montilla, respectively.

Fig. 3. Enslaved individuals admitted to San Juan’s Real Cárcel on April 6, 1845. Leg. 192, exp. 60.

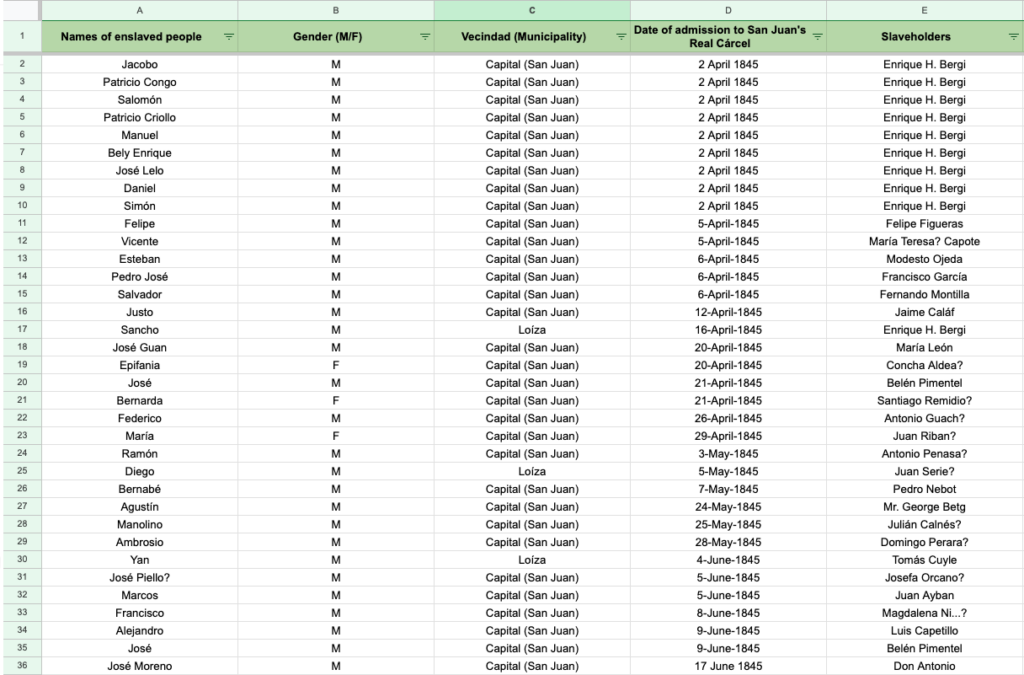

Drawing directly from the admissions lists, I created a live database with the available information of each enslaved person (fig. 4). The database is still in development, and the goal is for it to become publicly accessible. I was able to identify 238 enslaved individuals who entered the Real Cárcel between 1848 and 1868. According to Picó, the AGPR holds 172 nineteenth-century records of incarcerated enslaved people in San Juan.[7] The information compiled in this database, therefore, suggests that the actual number may have been significantly higher, although this does not necessarily mean that judicial records exist for each person. Moreover, it is possible that the admissions lists for earlier years and leading up to the 1873 abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico have been lost to time or are scattered across the AGPR’s Fondo Municipal de San Juan and other collections. This database is therefore inevitably fragmented, a condition that mirrors the violence and archival silences that so frequently shape the visibility of enslaved people in historical sources and that, in this context, are further intensified by incarceration.[8] Yet the database seeks to combat these archival power dynamics by serving as a space of growth in which the existing traces of incarcerated enslaved peoples’ lives can be gathered, revisited, made accessible, and expanded over time.

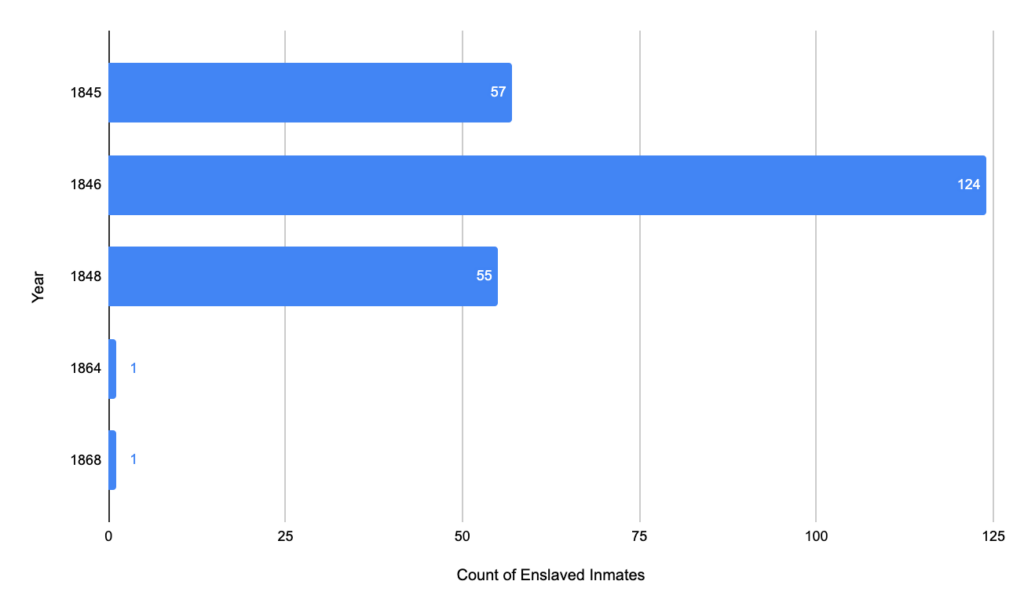

Based on the data I have gathered so far, I created a series of visuals (figs. 5-7) that offer a general overview of the incarcerated enslaved population. The majority of the sources in Legajo 192 do not offer insights about the circumstances surrounding the individuals they record. We are left without many details about their accusations, the conditions of their arrests, their judicial proceedings, and the duration of their sentences. Francisca’s arrest, for example, is one of the few better-documented cases in this collection. It would be valuable—indeed, necessary—as a future step for researchers to consult San Juan’s judicial records in the AGPR, as well as other municipalities linked to the origins of enslaved inmates. Jessica Álvarez Starr’s blog “Litigating for Liberty: Domingo’s Case as a Microhistory of Manumission in Mayagüez” has already taken important steps in this direction, showcasing the potential of the AGPR’s Real Audiencia Collection to illustrate how enslaved Africans and Afrodescendants litigated for their freedom in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico.

I hope this blog and its future database can serve as a foundational block—though still preliminary and imperfect—that invites broader collaborative projects that contribute to the PRAC’s initiative “Documentando la Historia de la Esclavitud en Puerto Rico en Contexto Caribeño.” My aim is also that it becomes a useful resource for researchers exploring this complex history.

Fig 4. Visual of the Database

Fig. 5. Municipal Origin and Number of Enslaved Inmates in the Real Cárcel, 1848-1868

| Vecindad (Municipality) of origin | Number of enslaved inmates |

| Capital (San Juan) | 189 |

| Río Piedras | 9 |

| Loíza | 6 |

| Toa Baja | 3 |

| Río Grande | 3 |

| Manatí | 3 |

| Fajardo | 3 |

| Luquillo | 2 |

| Guaynabo | 2 |

| Caguas | 2 |

| Bayamón | 2 |

| Trujillo Bajo | 1 |

| Trujillo Alto | 1 |

| Palo Seco | 1 |

| Naguabo | 1 |

| Mayagüez | 1 |

| Juncos | 1 |

| Humacao | 1 |

| Gurabo | 1 |

| Arecibo | 1 |

| Aguadilla | 1 |

| Not Indicated | 4 |

| Total | 238 |

Fig. 6. Gender Distribution of Enslaved Inmates

| Gender | Percentage |

| Female | 18.07% (43) |

| Male | 81.93% (195) |

| Total | 100% (238) |

Fig. 7. Yearly Count of Enslaved Inmates in San Juan’s Real Cárcel, 1845-1868

Notes

[1] Gonzalo Ramírez Sánchez, “Orden público en San Juan de Puerto Rico (1809-1820)”, Revista ECOS ASD 30, no. 26 (2023): 99-122; Guillermo Baralt, Esclavos rebeldes: conspiraciones y sublevaciones de esclavos en Puerto Rico (1795-1873), 4.ª ed. (Río Piedras, P.R.: Ediciones Huracán, 1996), 18-19.

[2] Jorell Meléndez-Badillo, Puerto Rico: A National History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024), 38. Also see Fernando Picó, Historia general de Puerto Rico (Río Piedras, P.R.: Ediciones Huracán, 2016), 187.

[3] Fernando Picó, El día menos pensado: historia de los presidiarios en Puerto Rico (1793-1993), 2nd ed. (Río Piedras, P.R.: Ediciones Huracán, 1998), 37.

[4] I wish to thank Ailish for her generosity in introducing me to this collection and showing me the AGPR’s staff facilities.

[5] Some sources show the constant communication between officials from San Juan’s Real Cárcel and correctional facilities in Río Piedras, Guayama, Trujillo Alto, Cayey, Guayanilla, Maunabo, Vega Baja, Loíza, Hatillo, Arecibo, Mayagüez, Río Grande, Guaynabo, and potentially many other municipalities.

[6] See Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995).

[7] Picó, El día menos pensado, 38.

[8] See Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995).