Documenting the Narratives of Puerto Rican Migration, 1945-1980

Introduction

Introduction

[This site is a work in progress. It will be constantly updated. Send us suggestions or comments.]

One priority of the Rutgers/PRAC, when it began its collaboration with the Archivo General de Puerto Rico, was to help organize the collections of the Department of Labor of both the Insular Government and the Commonwealth Government. This work provided the basis for a digitization project that included various other collections.

As an extension of their work on the Puerto Migration and diaspora communities, PRAC Director Aldo Lauria Santiago and Professor Ismael García Colón (College of Staten Island & Graduate Center, CUNY) were awarded a grant by Arte Publico Press’s Latino Digital Humanities Program to begin the digitization of migration-related documents at the Archivo General de Puerto Rico. The work has continued with the support of the Mellon Foundation. Three interns have been working on digitizing since May 2024. They continue carefully handling documents and selecting them for digitization under standards created by AGPR director Hilda Ayala and with the collaboration of archivist Pedro Roig. Victoria Arredondo, Iuliana Rosarioand, and Marchita Primavera have worked to digitize thousands of documents with the guides the PRAC created earlier for Department of Labor materials and with existing guides to the Fortaleza (Governors) collections.

This work will produce a publicly accessible digital archive that will be reproduced in three repositories and various guides and aides to the materials. Selection principles include:

- The uniqueness of the material.

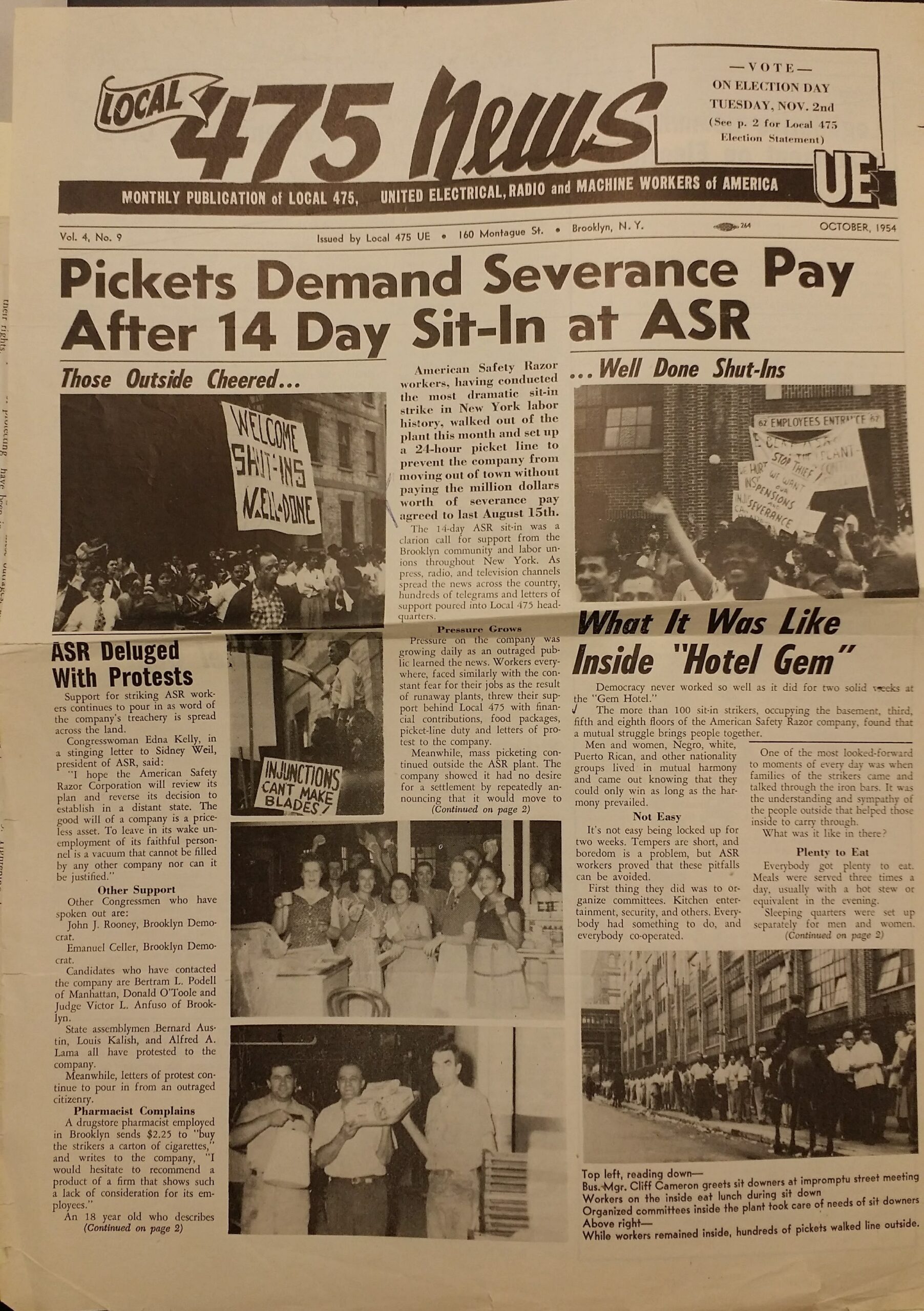

- How the material represents the work experience of migrants on farms, in factories, and other workplaces.

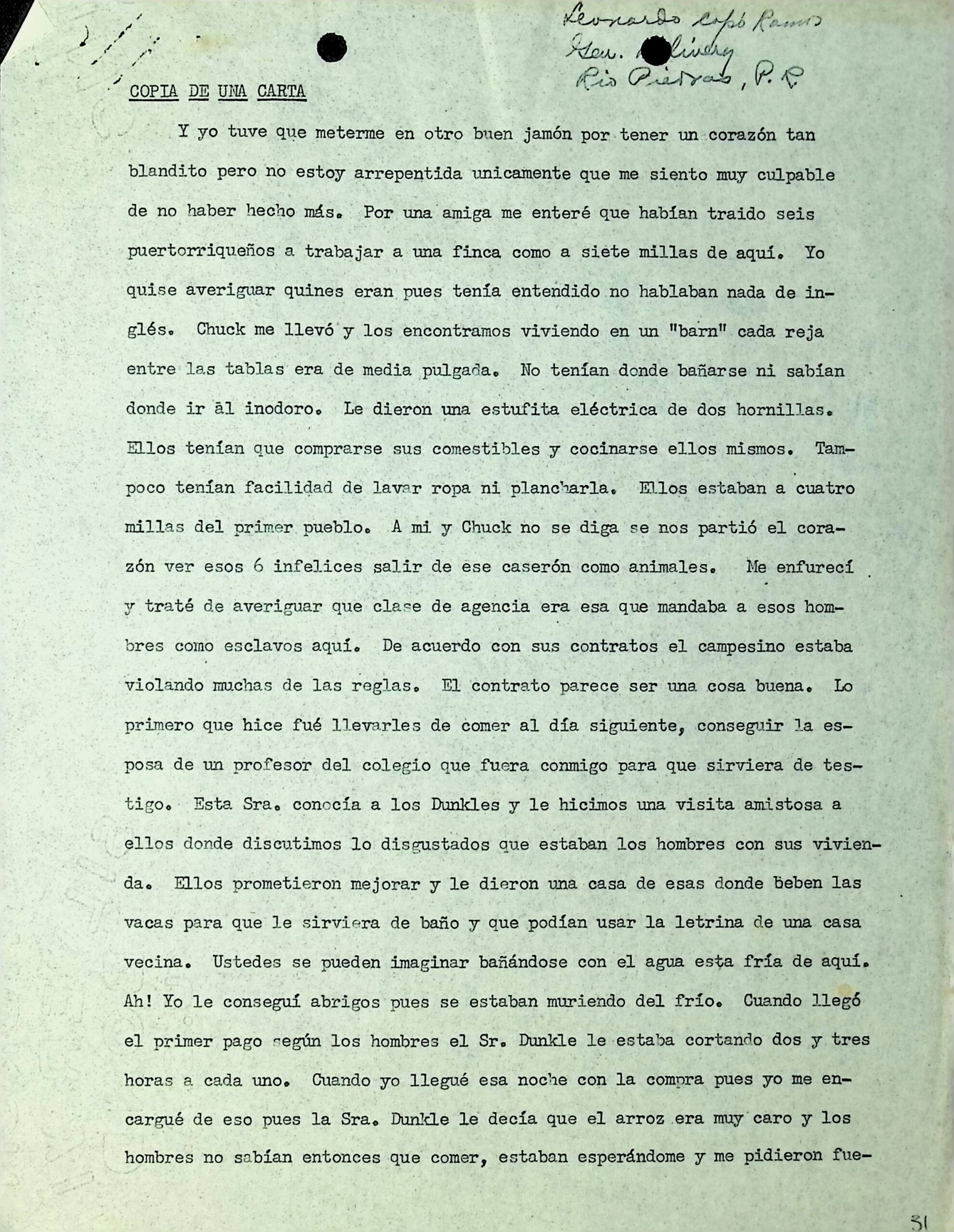

- How does the document represent voices or perspectives generated outside of the Department of Labor or state agencies?

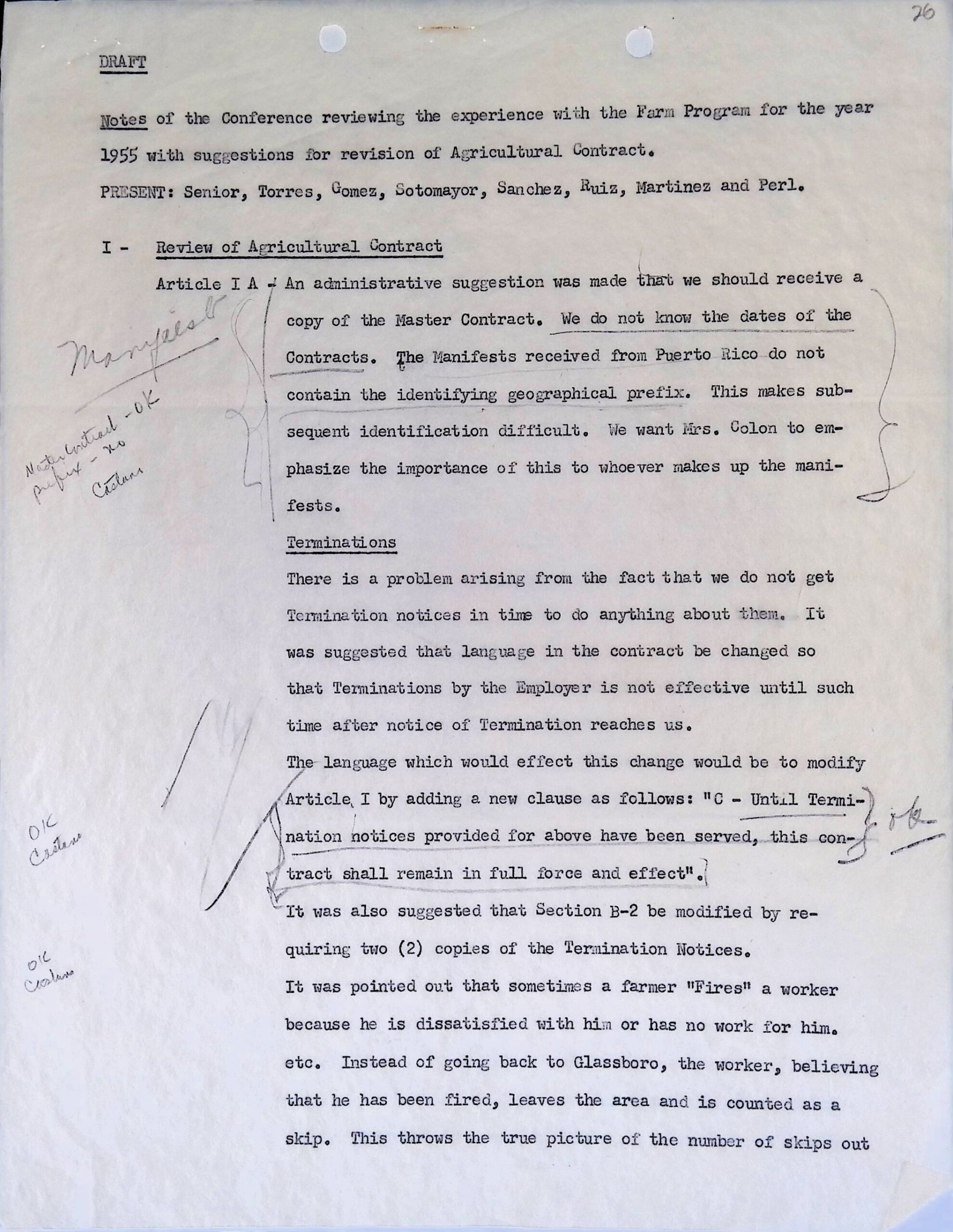

- How well it documents state and administrative practices.

These collections contain extensive materials relating to the migration process between World War II and the 1980s, including letters written by migrants and their families to Puerto Rican government officials. These materials include:

- Requests and other correspondence relating to Puerto Rican migrant workers (including seasonal contract farm laborers) in the US are held within the records of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor

- Reports and other data on the migration process produced by the Migration Division of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor

- Correspondence and other records relating to the internal discussions, debates, commissions, committees, and policies relating to migration produced by the Governor’s Office, the Labor Department, Fomento Economico, and other agencies, 1940-1980

Historical Context

The most recent scholarship on Puerto Rican migration has emphasized complex dynamics, many of which are rooted in Puerto Rico’s development and policies. The literature explores the efforts of the government of Puerto Rico to manage the migration of agricultural contract workers and domestic service workers while supporting the thousands of others who transitioned to life in New York and other cities.[1] These studies of Puerto Rican workers have focused on the problems encountered by migrants, unionization, contract labor, development, livelihood strategies, gendered labor, and transnationalism. In Sponsored Migration: The State and Puerto Rican Postwar Migration to the United States, Edgardo Meléndez documented the various roles played by the government of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor Migration Division. In Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire: Puerto Rican Workers on U.S. Farms, García-Colón traces the origin, development, and demise of the PRFLP and the impact of immigration policies on the Puerto Rican farm labor program. Meanwhile, Eileen Findlay’s book We Are Left without a Father Here: Masculinity, Domesticity, and Migration in Postwar Puerto Rico concentrates on the effects of farm labor policies on domesticity and masculinity using a transnational approach. Emma Amador’s work deals with the relationship of migratory policies to social services and domestic service employees.[2] Lilia Fernández describes how Puerto Ricans’ and Mexicans’ common sense of exploitation and discrimination transcends their differences despite being pitted against each other.[3]

This literature has made extensive use of materials held at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (especially the Migration Division papers known as OGPRUS). Still, these materials are well-organized and accessible. The less accessible Puerto Rico-based files complement and extend our knowledge of the migration process and have many clues to the policy decisions and lived experiences of Puerto Rican migrants during the last 100 years. In fact, the New York-based materials were part of a larger institutional framework established in Puerto Rico. The balance of the Migration Division papers reside within the archive of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor.

The role of the government of Puerto Rico in the migration of Puerto Ricans is central to examining Puerto Rican history. Despite this scholarship, most of the publications on Puerto Rican history have not utilized the resources we will digitize. As the historiography of Puerto Rican migration increasingly looks to comparative approaches in ethnic studies, the digitization of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor’s records will be essential to understanding the Puerto Rican experience in the United States.

Puerto Rican migration over the 20th Century was a complex phenomenon. This project does not aim to represent the diverse experiences, communities, and motivations related to the migration of Puerto Ricans to the US. This project focuses on how state policy and agencies intersected with this migration in the 1940-1980 period. Not all migrants were related to the agencies and leaders of Puerto Rico’s state. Even seasonal farm workers did not all connect with the official labor department farm worker program.

Framing Articles

Document Exhibit

Bibliographies

Teaching Materials

- Perez-Selles, Marla E., Ed.; And Others. Building Bridges of Learning and Understanding: A Collection of Classroom Activities on Puerto Rican Culture.

- Puerto Rican Perspectives. Lesson Plan Grades: 6-8, 9-12.

- Puerto Rican Migration. Lesson Plan.

- Puerto Rican Immigrants: A Resource Guide for Teachers and Students.

- Teach it: Post-World War II Puerto Rican Farm Labor Migration to Connecticut

Technical Details

Interns have worked digitizing the documents with an overhead document camera capable of producing high-resolution images (at least 300DPI) and presenting them properly with minimal metadata for collection origin and other basic characteristics, a process managed by Paula Roque.

The metadata model we use is based on the Dublin Core, which was implemented by Hilda Ayala.

The digital camera is the CZUR ET24, capable of producing JPG images at 330DPI.

Notes

[1] Eileen Findlay, We Are Left without a Father Here: Masculinity, Domesticity, and Migration in Postwar Puerto Rico (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014); Edgardo Meléndez, Sponsored Migration: The State and Puerto Rican Postwar Migration to the United States (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2017); Edwin Maldonado, “Contract Labor and the Origins of Puerto Rican Communities in the United States,” International Migration Review 13, no. 1: 106; Ismael García-Colón, Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire: Puerto Rican Workers on U.S. Farms (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020); John H. Stinson Fernández, “Hacia una antropología de la emigración planificada: El Negociado de Empleo y Migración y el caso de Filadelfia,” Revista de Ciencias Sociales 1, (June 1996): 112-155.

[2] Emma Amador, “Organizing Puerto Rican Domestics: Resistance and Household Labor Reform in the Puerto Rican Diaspora after 1930,” International Labor and Working-Class History 88 (2015): 67-86.

[3] Lilia Fernández, “Of Immigrants and Migrants: Mexican and Puerto Rican Labor Migration in Comparative Perspective, 1942-1964,” Journal of American Ethnic History 29, No.3 (2010): 6-39.