Early Transnationalization of Civil Society: The Flag of ‘Porto-Rico’

Santos Rivera-Cardona

Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science

Rutgers University, New Brunswick

PRAC 2025 Graduate Summer Intern

Much of the discussion surrounding the “Official Flag” of Puerto Rico has centered on the origins and the true color of the blue triangle in the flag. This discussion has led to numerous investigations, both by the state and individual scholars (Todd 1937; Natal 1970; Flores 2025). However, there is a gap in the literature regarding the agency of regular people, or civil society, both within and outside the archipelago, in addressing the issue of “no flag” in Puerto Rico. Thus, in this article, I will share some findings from weeks of archival research in the General Archive of Puerto Rico, made possible by the Rutgers Puerto Rico Archival Collaboration Program (PRAC) and the CLAS/RAICCS Student Research Grant. I hope to shed light on a different perspective regarding the discussion of Puerto Rico’s flag. Specifically, my goal is to demonstrate that the debate surrounding the flag has historically not only been an issue of internal/national politics but has also had broader international implications, to the point that non-Puerto Rican actors have contributed to the archipelago adopting an official flag.

Summer 2025: Archivo General de Puerto Rico (AGPR)

At the end of June, I traveled from New Jersey to Puerto Rico to begin my work at the General Archive of Puerto Rico. My main task was working on the Fondo Fortaleza, specifically the Sub-Fondo Governor Luis A. Ferré (1969-1972). Hence, one might ask, why are you discussing the flag of Puerto Rico? The reality is that I had some time to explore my areas of interest in tandem with my task of organizing Luis A. Ferré’s collection.

With the assistance of AGPR archivist Pedro Roig, I was able to locate several boxes that were already cataloged. In my search, I found folders that contained keywords such as flags or banderas, escudos or seals, national symbols or símbolos nacionales, among others.[1] After identifying the box numbers with these folders, Archivist Roig led me to the specific storage unit (depósito), shelf (hilera), row (tabilla), and ultimately to the boxes themselves.

Following our search, I was able to dive into the documents in box 1434. Box 1434 is what one might colloquially call a “Pandora’s box.” In this box, I found dozens of documents from state and non-state actors discussing the issue of “no flag” in Puerto Rico, dating back to the 1930s. Most of these documents are correspondence from various governmental and non-governmental organizations requesting that the government of Puerto Rico send a flag to be displayed at an event. Additionally, there are letters from people asking the government of the archipelago to address the issue of “no flag” in Puerto Rico. It should be noted that most of these letters included a copy of the government’s response to the organizations or individuals who had addressed the government regarding this matter. I will now outline this discussion and the implications for the history of Puerto Rico’s flag.[2]

“No flag” in Puerto Rico

The first thing that caught my attention when I started reviewing the documents in box 1434 was the dozens of letters sent to the government of Puerto Rico, specifically to the governor, requesting that a Puerto Rican flag be displayed at an event or building. Let me show some examples below:

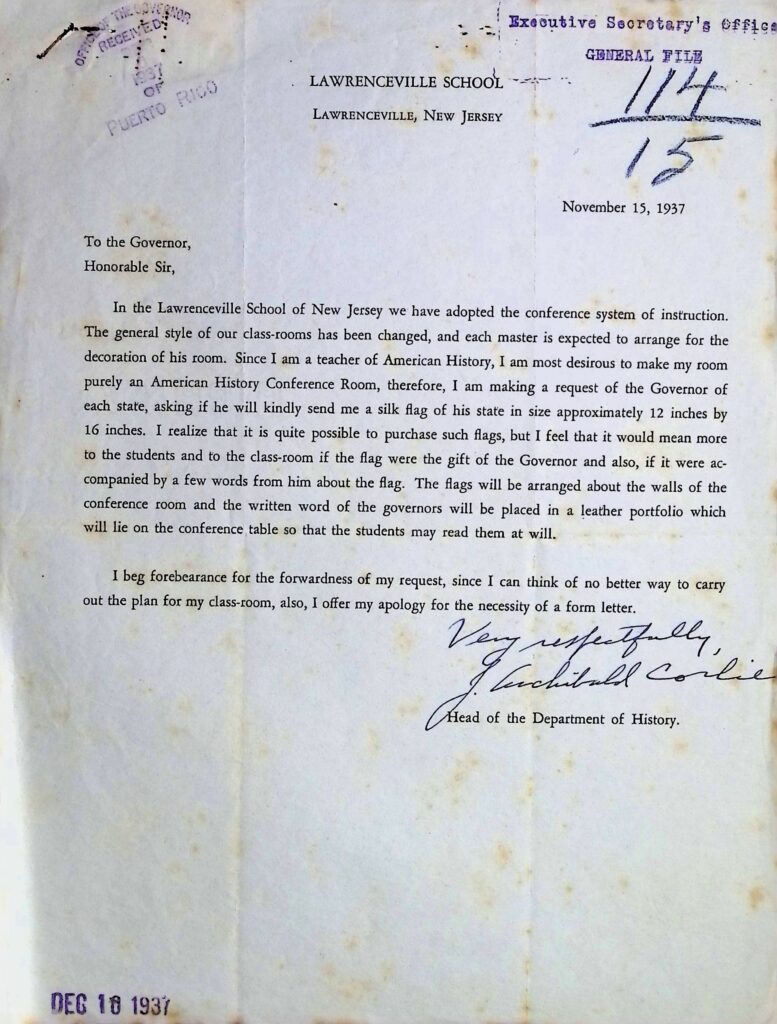

First, there is a letter from a school in Lawrenceville, New Jersey that dates to November 15, 1937 where the “Head of the Department of History” at Lawrenceville School writes to the governor of Puerto Rico if he could “kindly send a silk flag of his state” to display in his classroom with the goal of making it “purely an American History Conference Room” (see Image 1).

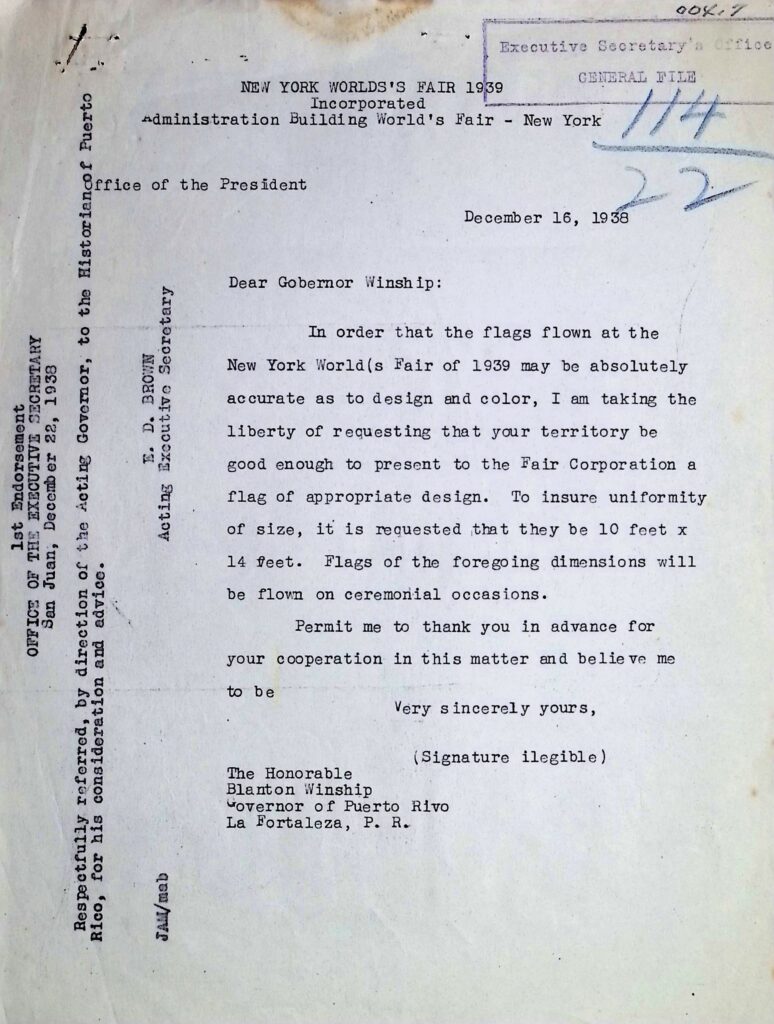

Second, I found a letter from December 16, 1938, by the Office of the President of the New York World’s Fair requesting the governor of Puerto Rico if the “territory be good enough to present to the Fair Corporation a flag [to be flown at the New York World’s Fair of 1939]” (see Image 2).

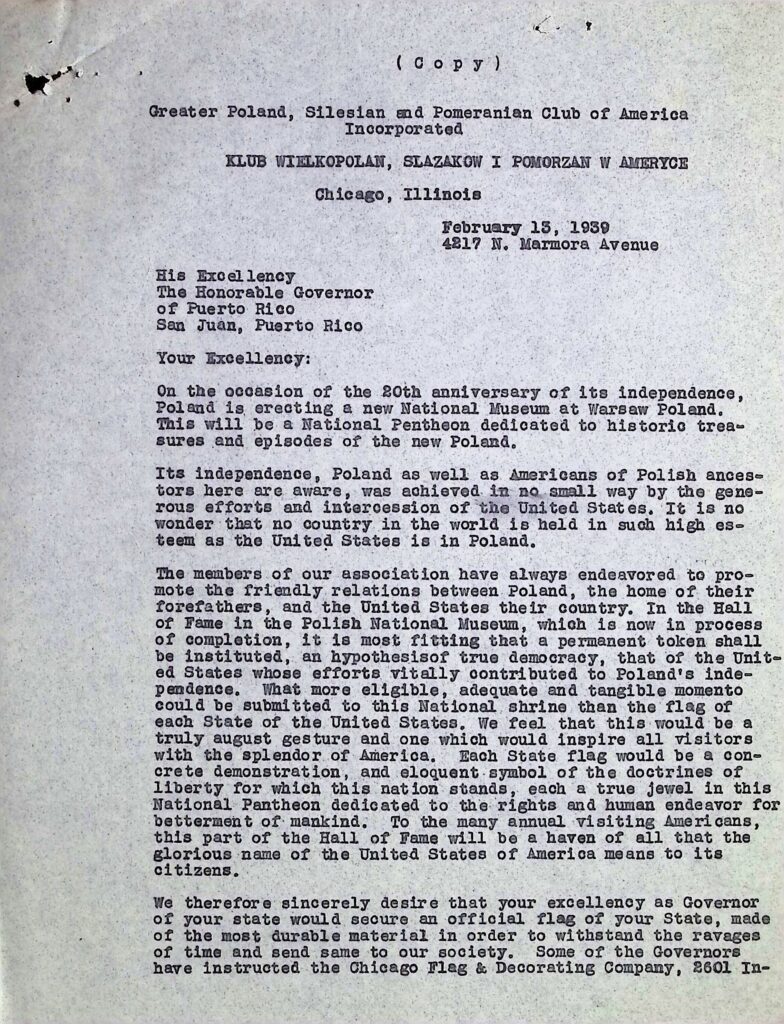

Third, there are letters from 1939 that the Greater Poland, Silesian, and Pomeranian Club of America Incorporated in Chicago, Illinois, sent to the Governor of Puerto Rico requesting a flag from the archipelago to display at the Hall of Fame in the Polish National Museum in Warsaw, Poland (see Image 3).

These request were followed by a response from the government of Puerto Rico stating that (1) Puerto Rico does not have an official flag, (2) The flag of Puerto Rico is just a white flag with the seal of the archipelago in the middle, and (3) the reason Puerto Rico did not have a flag is because “Puerto Rico is not an independent nation, but an organized territory of the United States, and as such the flag officially recognized here is the American Flag” (C. Gallardo, Executive Secretary, 1939). See some examples of government responses below:

Adopting an Official Flag for the Archipelago

The issue of “no flag” in Puerto Rico escalated to the point that civil society was urging the government to address the lack of a flag for the archipelago.[3] This is documented by numerous letters sent from different actors in society (e.g., lawyers, Puerto Rican and non-Puerto Rican citizens, among others) to the government. I will show some examples below:

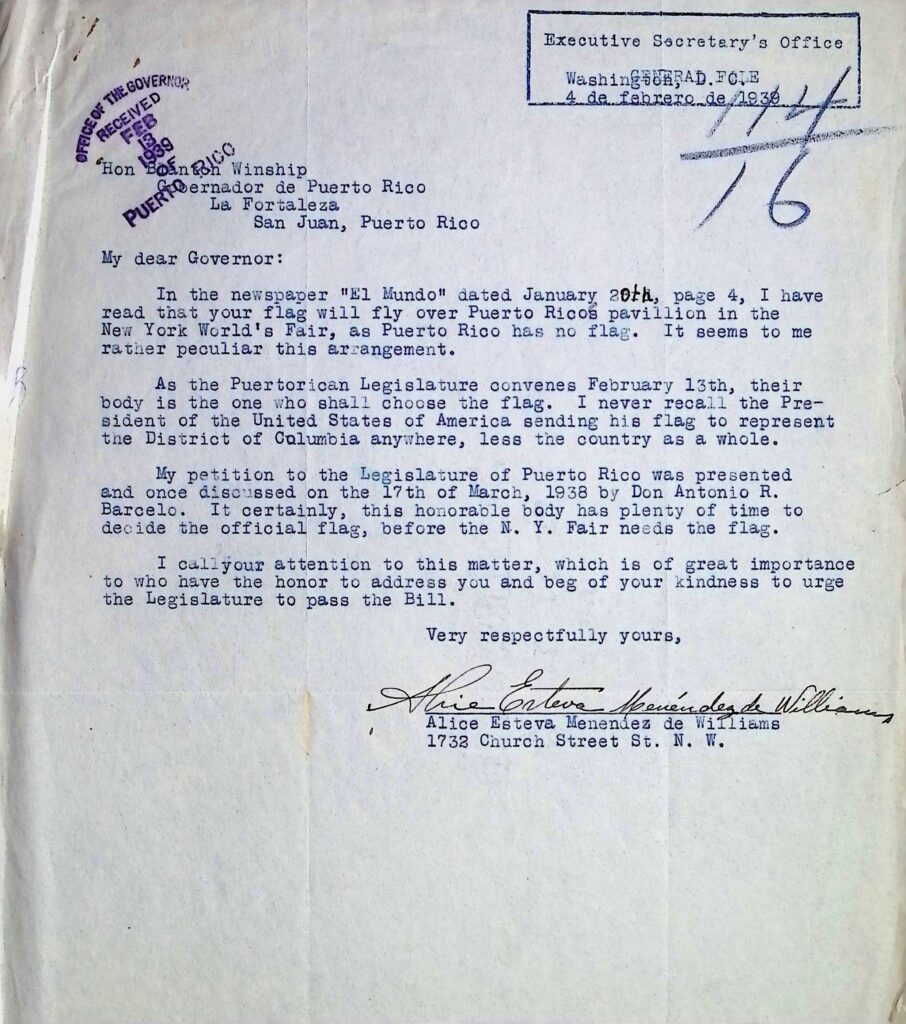

First, I found a letter from Alice Esteva Mendez de Williams, dated February 1939, in which she writes to Governor Blanton Winship after reading in the newspaper “El Mundo” that Puerto Rico will fly a “Governor’s flag” at the New York World’s Fair. Alice was surprised by this arrangement and petitioned the Legislature of Puerto Rico to decide on the official flag of the archipelago before the N. Y. Fair needed the flag. Specifically, Alice did not understand why the Governor of Puerto Rico was making the decision on which flag to display without first solving the issue of no flag in the archipelago (see image 7).

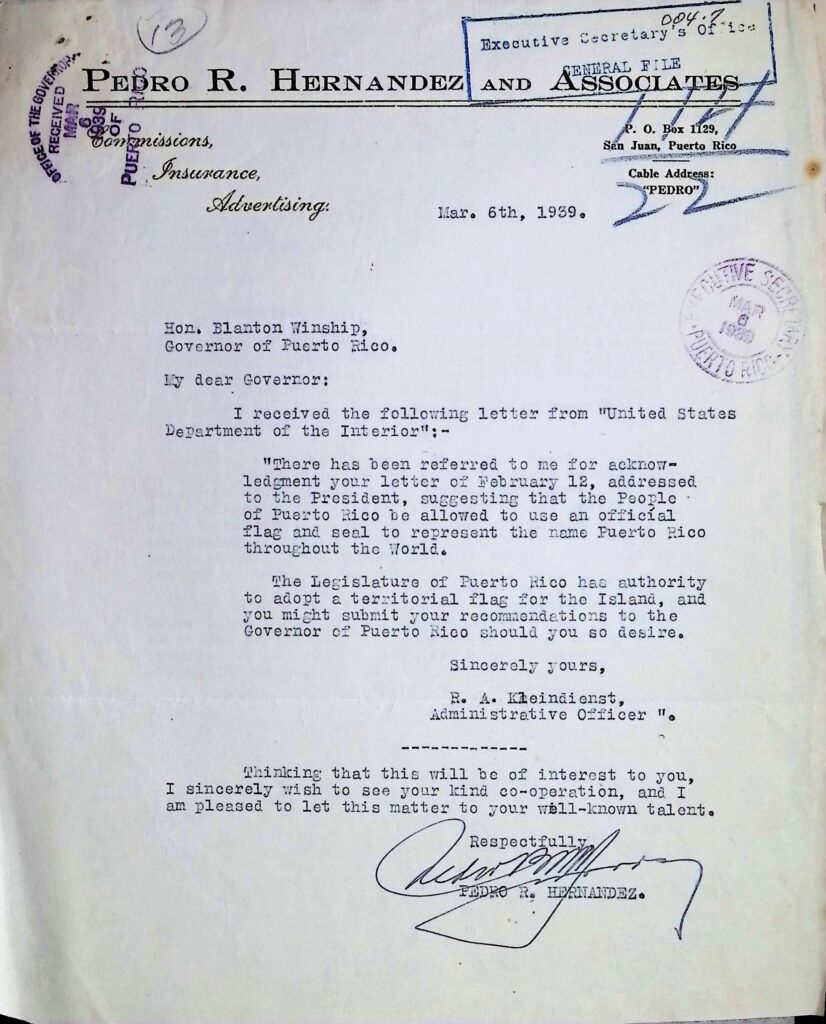

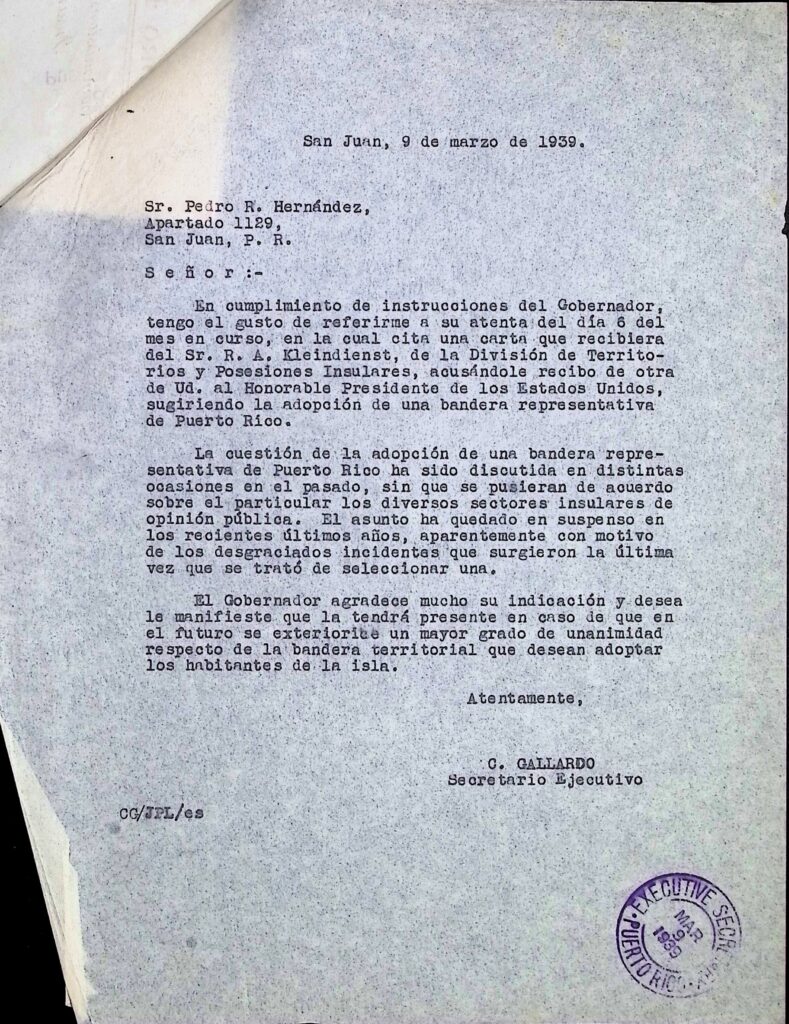

Second, I found a letter from March 1939, in which Pedro R. Hernandez and Associates wrote to the Governor of Puerto Rico, Blanton Winship, sharing some information from a letter the United States Department of the Interior had sent them. In such a letter, the U.S. Administrative Office of the Department of the Interior states that the Legislature of the archipelago has the authority to adopt a territorial flag for the Island, and people could submit their recommendation to the Governor of Puerto Rico if they desired (see image 8). Following the government’s receipt of this letter, Pedro Hernandez and Associates were informed by the executive secretary of Puerto Rico, C. Gallardo, that the Governor of Puerto Rico appreciated the information provided and would take into consideration his message whenever the inhabitants of the island decided to adopt a territorial flag (see image 9)

These documents demonstrate that civil society exerted a degree of agency in attempting to resolve the issue of no flag in Puerto Rico. While I am only showing two documents, I was able to collect dozens of letters from other citizens inquiring about the flag of Puerto Rico and seeking information on whether the Legislature of the archipelago had addressed the issue of having no flag. Moreover, one can notice that these letters were not only sent to residents of the archipelago, but also to people living outside of Puerto Rico who also wanted to know when and how the issue of no flag would be resolved.

However, I should note that the issue of no flag was not an issue that happened in the 1930s. In fact, I found documents from the beginning of the century where people were actively writing to the government of the island to solve the issue of no flag in Puerto Rico. I will outline them below.

The Flag of ‘Porto Rico’

Up to this point, the documents I have shown date to the mid-1930s; however, I also encountered documents from the beginning of the century that shed some light on how the discussion around the flag of Puerto Rico was some years after the archipelago had been invaded by the United States of America.

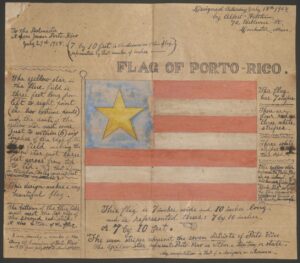

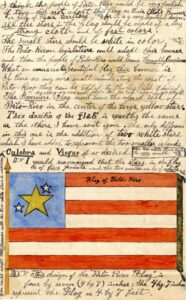

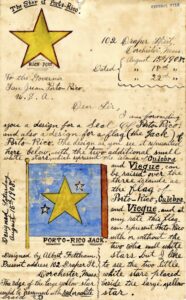

During the summer of 1908, Albert Feltham, a resident of Dorchester, Massachusetts, began sending some designs he had created to the Postmaster and the Governor of Puerto Rico. Albert sent approximately ten designs of the Flag of ‘Porto-Rico,’ the Territorial Seal of ‘Porto-Rico,’ the ‘Porto Rico’ Custom House Flag, the ‘Porto-Rico’ Merchant Flag, and the Pilot Flag of ‘Porto Rico.’ These are all different symbols Albert had designed with the hope that the government of Puerto Rico would adopt them as official national symbols for the archipelago. In Albert’s own words, writing to the Governor of Puerto Rico, “It has been my desire, and very many times I have thought of it, that ‘Porto-Rico’ should be represented in some manner as a territory, if not a state, in the American union” (August 31st, 1908). For Albert, ‘Porto-Rico’ could only become thoroughly American in practice and character once it had officially adopted [his] national symbols; representing itself with a territorial or State banner and Seal of their government.

Albert was confident that ‘Porto-Rico’ should adopt the symbols he proposed to the point that he wrote to the Governor stating that “… the people of Porto-Rico would be very foolish if they did not adopt this flag as their State Banner or flag of their territory, for it is a very beautiful design” (August 31st, 1908). Ultimately, Albert acknowledged it was the Legislature’s duty to adopt these symbols to achieve what he thought was Porto-Rico’s right to representation.

Albert’s designs address several important yet often overlooked aspects of Puerto Rico’s history and political situation. First, many of his designs are characterized by the inclusion of Vieques and Culebra as part of ‘Porto-Rico,’ hence the use of three stars instead of one in the flag. Second, his designs, use of colors, and size all have deep historical and political meanings that transcend the mere usage of a national symbol. Albert was deeply committed to showcasing through his designs the rich history and significance of Puerto Rico to the American union. Finally, Albert’s symbols exemplify the agency non-state actors had in the issue of no flag in Puerto Rico.

Albert Feltham: The Flag of Porto-Rico

Conclusion

In this article, my goal has been to offer a new perspective on the historical and political debate surrounding the flag of Puerto Rico. Besides the ongoing debate over the “correct” color of the triangle and the true creator of the flag, I aimed to illustrate through archival research another story that has never been told. Thus, I argue that the controversy has never been solely a matter of internal or national politics; instead, the debate surrounding the flag of Puerto Rico has carried significant international dimensions. To this extent, I have demonstrated that numerous non-Puerto Rican actors, such as Albert Feltham (1908), and various international organizations played a crucial role in the process of adopting an “official” flag for Puerto Rico.

Moreover, this article demonstrates that at the beginning of the 20th century, signs of an early transnational civil society emerged, existing both within and outside Puerto Rico, which was concerned about the issue of having no flag in the archipelago and actively sought to resolve it. Consequently, the historical and political trajectory of national symbols in Puerto Rico necessitates a new assessment that considers the role these actors played in the process of adopting national symbols in Puerto Rico.

To conclude, I want to reiterate my appreciation to the Rutgers Puerto Rico Archival Collaboration Program (PRAC) and the CLAS/RAICCS Student Research Grant for making this project possible. I would like to thank the staff at the General Archive of Puerto Rico (AGPR) and all the staff/interns of the Rutgers-Puerto Rico Archival Collaboration Program (PRAC), who, with scarce resources, preserve the history of our nation. Finally, thanks to Professor Aldo Lauria Santiago for his mentorship, tireless efforts, and commitment to preserving and sharing the history of Puerto Rico.

¡Seguimos!

References

Flores, Joseph Harrison. 2025. La Historia De La Bandera De Puerto Rico. Del Conflicto a La Certeza: Archivo Digital Nacional de Puerto Rico.

Kopecký, P. and Cas Mudde. 2003. “Rethinking civil society.” Democratization, 10(3). 1–14.

Natal, Carmero Rosario. 1970. “El Debate Sobre El Origen De La Actual Bandera Puertorriqueña.” Revista del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, (Enero – Marzo 1970). 44–49.

Todd, Roberto H. 1937. “La Génesis De La Bandera Puertorriqueña.” Ateneo Puertorriqueño.

[1] I also thank Víctor M. González Sosa (AGPR Work Coordinator for Rutgers/PRAC) for sharing the images of the flags that I will display below. Thank you, Víctor, for sharing your findings so kindly.

[2] I am only showing a small portion of the documents I found in the archive. I digitized over 160 pages on the subject. Hence, if you would like to look at the rest, please send an email to Professor Lauria.

[3] Civil society can be defined as the “organized collective activities that are not part of the household, the market (or more general economic production), and the state” (see Kopecky and Mudde 2010).