Litigating for Liberty: Domingo’s Case as a Microhistory of Manumission in Mayagüez

Jessica Alvarez Starr

Ph.D. Student in History, Emory University

PRAC Summer Mellon Intern, 2025

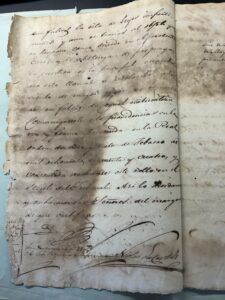

Tucked away amidst the writings of escribanos públicos and documents certified by local notaries, within one unassuming box of the hundreds held in the Real Audiencia Collection in the Archivo General de Puerto Rico (AGPR), lies what remains of a civil case brought by Domingo.[1] Despite his role as a primary litigant in the legal proceedings recounted therein, Domingo is only referred to by his first name and his present legal status of enslavement, with the label of ‘slave’ always appearing alongside his name as if an intrinsic modifier of his being. Beyond his enslaved status, the documents reveal little personal information about this man, where he came from, or how he came before the Spanish Crown’s courts in search of freedom. A brief first reading of the documents affords basic identifying details: Domingo has been enslaved by Don Antonio Carrera in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, and has brought a civil suit against him in hopes of obtaining freedom. We do not know, however, if Domingo was born into enslavement on the archipelago or captured somewhere in the African continent and trafficked across the Atlantic, how long he has been held in captivity, or what he has endured up until his petition for emancipation. Here begins the work of the historian to honor Domingo’s life, build beyond the content of colonial records, and situate this one man’s efforts to achieve legal liberation within the broader struggle for emancipation.

Recurso de súplica, AGPR, Audiencia Territorial, Real Acuerdo, Caja 19-A, Exp 24

On the island’s western coast, Mayagüez — granted the title of villa by the colonial government in 1836 — was just one of the many sites where enslaved men and women fought for freedom in Puerto Rico. The mountainous terrain and rich soil contributed to the region’s wealth in the agricultural and mining sectors. Still, the labor of the individuals enslaved in this territory afforded the local landed elite economic and political power. The entrenched nature of labor exploitation extended beyond large-scale sugar plantations, ingenios, which have featured prominently in the historiography on slavery in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico, to local coffee fincas, smallholdings, or skilled trades, and the domestic sphere.[2] Slavery pervaded across various sectors, but was particularly prominent in the sugar and coffee production and port functions of mid-century Mayagüez, then one of the island’s principal commercial hubs.

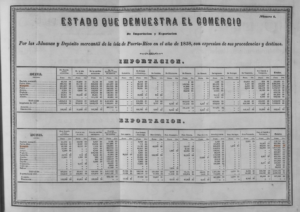

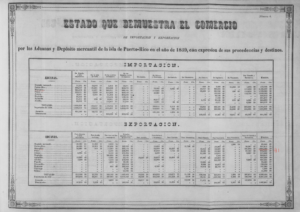

Following devastation from earthquakes, hurricanes, and the so-called Great Fire of 1841, reconstruction efforts and urban reforms aided the local landed elite in reestablishing themselves and the city as a profitable center of agricultural production and mercantile activity.[3] In fact, data from the Balanza mercantil de la isla de Puerto Rico for the years of this civil suit, 1858 to 1859, reveals that Mayagüez was either the first or second most productive port based on total exports.[4] High rates of production and exportation relied on the labor of enslaved individuals. They resulted in increased profits for enslavers, solidifying the system of slavery as crucial for maintaining the economic and sociopolitical status quo. Although deeply entrenched and defended by many Mayagüezanos, especially those who personally profited from owning human property, slavery also faced constant challenges from the very people it held in captivity. Across the archipelago, since the early moments of slavery in the conquest and colonization of Puerto Rico, enslaved individuals had engaged in various forms of resistance to contest captivity and seek freedom for themselves and others. These efforts can be considered emancipatory practices, even when they do not result in complete legal emancipation for the individual in question.

Among enslaved Africans and their descendants in Mayagüez, many of whom had been barred from education and denied the privilege of literacy, emancipation strategies manifested in multiform practices. As elsewhere in Puerto Rico and other slave societies, enslaved people used various emancipation strategies to resist enslavement on individual, communal, and institutional levels, from quotidian acts of refusal to collective flight or violence against oppressors. Common strategies employed at a personal level are aimed not at complete legal freedom but rather at improved daily living conditions. These included feigning illness or injury to avoid forced labor, participating in religious or spiritual practices to provide a sense of protection and comfort, and running away for short periods. Such instances of quotidian antislavery acts rarely make it into the official archival records. Still, evidence of resistance can be traced in runaway advertisements published in local newspapers, minor criminal cases of theft, violence, or injuries tried before district courts, and church records of marriages and baptisms that reveal kinship networks and family formation.

In addition to individual, quotidian acts of refusal and resistance, enslaved people sought opportunities for manumission — a form of emancipation through legal means, often resulting in official documentation from secular, civil courts or ecclesiastical institutions — via mechanisms such as self-purchase, military service, or in the last wills of their enslavers upon death. Freedom through manumission frequently occurred on an individual level. However, legislation could enact broader changes to the institution of slavery, such as the Moret Law, which declared all children born to enslaved mothers after 1870 to be free.[5] While the written law offered certain avenues for manumission and afforded enslaved individuals certain legal rights, it did not guarantee that such procedures would be observed appropriately. In fact, the persistent conflicts between written legal codes and actual lived realities of enslavement mark one of the main driving forces behind enslaved individuals’ engagement with the judicial system across Puerto Rico. As people sought to improve their conditions and access to degrees of freedom or rights, many looked to the law as a resource and actively engaged in litigation. Enslaved individuals brought petitions before district courts to protest discrepancies between legal codes regulating enslavement and their experiences, taking recourse in the judicial system to protect rights prescribed under Spanish legislation, from laws limiting the extent of corporal punishments permitted to those restricting family separations for married couples and children recognized by the Church. Enslaved litigants brought pleitos, or civil suits, before local courts to address abuses, achieve specific objectives such as the right to contract themselves out for wage labor for a certain amount of time each week, and even petition for full manumission. Despite the many barriers limiting enslaved individuindividuals’to judicial institutions, including restrictions on mobility, literacy, and time imposed by slaveowners and the broader colonial system, municipal records reveal their significant, complex interactions with the law and local courts. Domingo’s suit against his enslaver, Don Antonio Carrera, illustrates one of the many civil cases brought by enslaved litigants seeking freedom before the judicial system in Puerto Rico and offers insight into the complex processes and negotiations involved therein.

As just one of several surviving pleitos held in the AGPR, Domingo’s case presents the individualized nature of civil litigations for freedom, yet also reveals prominent figures who reappear across multiple suits as well as standardized legal phrasings and references to specific legislation that informed the broader context of manumission in Mayagüez and other municipalities. For this case, the lawyer who helped Domingo to bring his petition before the juicio del ayuntamiento de Mayagüez was licenciado Don Segundo Ruiz Belvis, an important abolitionist and independence leader. Born in the neighboring municipality of Hormigueros in 1829, Ruiz Belvis was appointed to serve as síndico for Mayagüez starting in 1858, the same year as Domingo’s case, a position, which he used to advocate for enslaved individuals in freedom suits before the courts. In addition to his later, more recognized antislavery and anticolonial activism, Ruiz Belvis’ Belvis’ a lawyer afforded him hands-on experience with the intricacies of legal manumission processes, directly impacting the enslaved litigants for whom he campaigned and shaping his own abolitionist ideologies with intimate knowledge of the struggles for freedom against slavery as an entrenched institution that many elites and officials conspired to uphold through the same judicial system.

From Domingo’s case, we also learn of prominent figures on this side of the suit, such as the then Teniente Alcalde Mayor of Mayagüez, Don Bartolomé Janer. Following the favorable ruling for Domingo, including the dismissal of an appeal for annulment brought by Carrera, Janer filed a complaint against Ruiz Belvis before the Real Audiencia alleging that the lawyer obstructed the case and caused an erroneous judgment. Despite this claim, the court upheld the case in favor of Domingo, as one of various suits brought by Ruiz Belvis during his office as síndico del ayuntamiento. From this position, Ruiz Belvis provided legal support for enslaved individuals seeking freedoms and rights before the judicial system, advocacy that frequently placed him into conflict with the slaveholding elites and local colonial officials, oppositions which played out in both the legal arena and the clandestine press.[6] This suit also suggests the complexity of the legal process, particularly for matters as contentious as the manumission of enslaved individuals, from the multiple súplicas spanning months and years to the discussion of various legislative acts and decrees concerning practices of enslavement, emancipation, and execution of judicial authority.

Despite their value, the documents generated by these legal proceedings leave much to be considered. Most notably, they do not capture the extralegal actions surely taken by Domingo for him even to access the local court, much less have his case brought before the Real Audiencia by Ruiz Belvis. Systemic barriers hindered enslaved individuindividuals’to the legal system and, for those who did succeed in bringing litigation, reduced the likelihood of achieving their objectives through such official means. As a result, many people pursued alternative methods of resistance to seek freedoms, from the aforementioned quotidian acts of refusal to collective forms of escape and rebellion. Efforts to escape enslavement by running away, either through petit marronage or grand marronage — the former defined as individuals or small groups fleeing for short periods of time before returning and the latter when people permanently fled captivity and established their freedom by seeking refuge in maroon communities or through assimilation into free Afro-Puerto Rican communities — are underrepresented in archival sources given the need for secrecy as an act of survival. Additionally, criminal records reveal that enslaved individuals engaged in acts of violence and organized collective uprisings against their oppressors, despite dominant narratives characterizing the enslaved population of Puerto Rico as more docile and passive than people in surrounding territories.[7] The difficulties in accessing judicial institutions and achieving favorable outcomes in legal proceedings led many enslaved individuals to turn elsewhere for manumission.

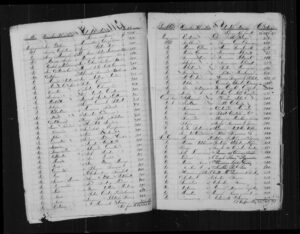

Whether Domingo engaged in extralegal strategies to seek emancipation before bringing his civil suit to the courts remains unclear. Still, supplemental sources situate litigation as only one of many methods by which enslaved people pursued manumission. In the case of Mayagüez, a census registry from 1873 lists the names of enslaved residents and the prices ascribed to them, revealing the “valor d” la coartación” or the”monetary value required for each person to achieve manumission through self-purchase.[8] Neither Domingo nor his enslaver appears on this registry, possibly suggesting that Domingo established himself as a free man elsewhere following his suit and that his former owner either moved or no longer held human captives by the eve of abolition in 1873. While there is much left to the imagination with the aftermath of this pleito, particularly concerning Domingo’s post-emancipation trajectory, the case is a valuable example of how formal, legal mechanisms of manumission allowed enslaved individuals to gain freedom. The case offers insight into the function of the municipal council, or ayuntamiento, and the roles of various agents involved in the judicial processes, demonstrating the complexities of such legal proceedings and, ultimately, the possibility for petitioners to become freed in the eyes of the law.

Notes

[1] “Recurso de súplica”, Archivo General de Puerto Rico, Fondo Audiencia Territorial de Puerto Rico, Subserie Real Acuerdo, Caja 19-A, Expediente 24.

[2] Prominent works on slavery in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico focusing on sugar plantation regions as central sites include Luis Díaz Soler, Historia de la esclavitud negra en Puerto Rico (Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1965), Andrés Ramos Mattei, La hacienda azucarera: Su crecimiento y crisis en Puerto Rico, siglo XIX (Cerep, 1981), Francisco Scarano, Sugar and Slavery in Puerto Rico: The Plantation Economy of Ponce, 1800-1850 (University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), and Luis Figueroa, Sugar, Slavery, & Freedom in Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico (University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

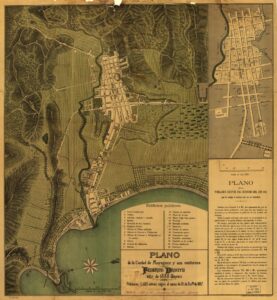

[3] For more on the Great Fire of 1841, its impacts, and subsequent efforts to rebuild Mayagüez, see Ramonita Vega Lugo, “El desa”rollo de Mayagüez después del Fuego Grande de 1841,” link. “ee also an 1888 map of Mayagüez, particularly the part labeled “Plano d” la población después del incendio del año 1841 que la redujo a cenizas casi en su totalidad,” Librar” of Congress, link.

[4] In 1858, Mayagüez recorded 977,514 pesos in total exports, second only to Ponce. In the year of 1859, Mayagüez surpassed Ponce with the highest rates of total exports, a recorded 1,004,083 pesos worth. See Balanza Mercantil de la Isla de Puerto Rico (Imprenta de Acosta, 1859 and 1860), available on Digital Library of the Caribbean, link 1 and link 2.

[5] For more on the Moret Law, see “The Free Womb Project,” https:”/thefreewombproject.com/puerto-rico/.

[6] For more on the conflict between Ruiz Belvis and Janer, as well as the role of the clandestine press in abolitionist movements in Mayagüez and beyond, see Mario R. Cancel, “Sociedaes secretas: Mito y realidad. El caso de Segundo Ruiz Belvis,” Horizontes 34, no. 67 (1991): 49-61.

[7] For a general overview of instances of collective rebellion by enslaved individuals in Puerto Rico, see Guillermo A. Baralt, Esclavos rebeldes: Conspiraciones y sublevaciones de esclavos en Puerto Rico (1795-1873) (Ediciones Huracán, 1989).

[8] “Registro de esclavos”, Documentos Municipales, Caja 334. Scans available on Family Search, Film #008138869, Image 1370-1372, https://www.familysearch.org/en/search/film/008138869?cat=605453&i=0.