Print Media and the New Status: The Dorvillier Newsletter Conceptualizes Puerto Rico’s Development, 1953-1959

Victor A. Cruz

Ph.D. Student in History, Binghamton University, SUNY

PRAC Summer Mellon Intern, 2025

Introduction

Between 1950 and 1952, Puerto Rico and the United States further redefined their colonial relationship as an Estado Libre Asociado (ELA), commonly referred to as the commonwealth status. The early years of the commonwealth were particularly interesting because the outcome of the status was yet to be determined, and the vision of what Puerto Rico would ultimately become as an ELA was still in its infancy. While the new status confirmed that Puerto Rico would adhere to U.S. hegemony, it raised questions about how the material conditions on the island would evolve and what the new status would ultimately mean for industry and families on the island. As Puerto Rico transitioned from agricultural labor to industrialization, a project already underway but now further solidified, business and capital became increasingly crucial to Puerto Rican political leaders who sought to modernize the island in line with their perceived image of progress, and overseas investors sought to insert themselves within the emerging economy. Conversations about industrial development, investments, wealth, migration, and labor instability evolved from topics of interest to common themes in Puerto Rico’s development.

Between 1950 and 1952, Puerto Rico and the United States further redefined their colonial relationship as an Estado Libre Asociado (ELA), commonly referred to as the commonwealth status. The early years of the commonwealth were particularly interesting because the outcome of the status was yet to be determined, and the vision of what Puerto Rico would ultimately become as an ELA was still in its infancy. While the new status confirmed that Puerto Rico would adhere to U.S. hegemony, it raised questions about how the material conditions on the island would evolve and what the new status would ultimately mean for industry and families on the island. As Puerto Rico transitioned from agricultural labor to industrialization, a project already underway but now further solidified, business and capital became increasingly crucial to Puerto Rican political leaders who sought to modernize the island in line with their perceived image of progress, and overseas investors sought to insert themselves within the emerging economy. Conversations about industrial development, investments, wealth, migration, and labor instability evolved from topics of interest to common themes in Puerto Rico’s development.

Print media plays a role in understanding the development of these themes, and with that comes the Dorvillier News Letter, also known as the Dorvillier Business News Letter. The Dorvillier News Letter was founded by Massachusetts native William J. Dorvillier in 1953. Dorvillier is better known for creating the San Juan Star, which, under his supervision, would win the Pulitzer Prize in 1960 for criticizing Catholic bishops for forbidding Catholics from voting for the Popular Democratic Party.[1] While the San Juan Star is what Dorvillier is most known for, the Dorvillier News Letter is of particular interest due to its role as an English news source focused on business and investment developments in Puerto Rico during the early years of the ELA.

Print media plays a role in understanding the development of these themes, and with that comes the Dorvillier News Letter, also known as the Dorvillier Business News Letter. The Dorvillier News Letter was founded by Massachusetts native William J. Dorvillier in 1953. Dorvillier is better known for creating the San Juan Star, which, under his supervision, would win the Pulitzer Prize in 1960 for criticizing Catholic bishops for forbidding Catholics from voting for the Popular Democratic Party.[1] While the San Juan Star is what Dorvillier is most known for, the Dorvillier News Letter is of particular interest due to its role as an English news source focused on business and investment developments in Puerto Rico during the early years of the ELA.

The Value of the Dorvillier News Letter

The Dorvillier News Letter presents itself as a neutral source for “businessmen,” while also providing a snapshot in time and insight into the conversations being had by investors, labor, political leaders, and businesspeople. For those interested in the collection, the Dorvillier News Letter should be understood in its context; as a limited source of print media that should not be taken as wholly factual or authoritative, instead the Dorvillier provides potential topics of interest, data points, and a perspective that informs us of what was perceived to be of particular interest to English-speaking investors through the eyes of one the most prominent editors of English print media in Puerto Rico; take from that what you may.

The Dorvillier goes over various economic developments and financial matters beyond the scope of my expertise. Rather than attempt to historicize the extensive economic and political information found throughout the Dorvillier, this blog will briefly overview several broad topics readers can expect to see throughout the newsletter in hopes of drawing interest to the collection. Those interested in reviewing this collection can find various issues scattered throughout the collections at the Archivo General y Biblioteca Nacional de Puerto Rico, or see the complete collection at the Biblioteca y Hemeroteca Puertorriqueña (formerly the Colección Puertorriqueña) at the University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras (UPRRP).

The Broad Topics

The Dorvillier functions as an interconnected collection of newsletters. The topics of one issue may be directly referenced in a later issue when a development occurs. The earliest issue of the Dorvillier in the Biblioteca y Hemeroteca Puertorriqueña was released on November 7, 1953. The newsletter’s first issue sets the foundation for what many of the future editions are focused on, such as industrial investments throughout the island, labor strikes and union organizing, home ownership, policy changes, tax structures, and imports/exports.

The Dorvillier functions as an interconnected collection of newsletters. The topics of one issue may be directly referenced in a later issue when a development occurs. The earliest issue of the Dorvillier in the Biblioteca y Hemeroteca Puertorriqueña was released on November 7, 1953. The newsletter’s first issue sets the foundation for what many of the future editions are focused on, such as industrial investments throughout the island, labor strikes and union organizing, home ownership, policy changes, tax structures, and imports/exports.

An example of what can be expected throughout The Dorvillier’s reporting is seen with the electronic industries in the newsletter’s first issue. It opens with, “Some free-wheeling businessmen are in for a shock.” This is in response to the electronic market shifting from “foreign” to “domestic” and, in doing so, setting up standards for imports. This is framed as a response from Puerto Rican consumers who have been the target of faulty electronic merchandising due to their status as a foreign market. Alongside implementing regulatory standards on electronics, the newsletter brings attention to a shift in labor demands. The market is shifting for both consumers and workers. It is no secret that Puerto Rico was once a hub for the textile and needlework industries. Still, it is clear that there is a “swing to electronic industries,” and Weston Electric and Philco indicate this shift.[2] Both were American-based electronic manufacturers that were in the process of negotiating contracts with the government-owned Puerto Rico Industrial Development Company, more commonly known as Fomento.

The Dorvillier News Letter often speculates whether business will continue to grow or see a decline during the upcoming months. In this section (Left), we see optimism from the private and public sectors in infrastructure development. On the other hand, a fear stems from the unstable sugar industry. While the electronic industry saw investment and growing interest, the sugar industry was riddled with questions involving labor loss and farm liquidation. Seeing that the sugar industry inevitably collapsed, some critics’ early pessimism became true.[3]

The Dorvillier News Letter often speculates whether business will continue to grow or see a decline during the upcoming months. In this section (Left), we see optimism from the private and public sectors in infrastructure development. On the other hand, a fear stems from the unstable sugar industry. While the electronic industry saw investment and growing interest, the sugar industry was riddled with questions involving labor loss and farm liquidation. Seeing that the sugar industry inevitably collapsed, some critics’ early pessimism became true.[3]

While the newsletter does lean towards economic optimism, it does bring attention to the growing concerns with labor loss. The juxtaposition between the optimism of economic growth and the pessimism of workers is at the forefront of much of the dialogue. For example, while one article in the November 7th issue opens with “Liquidation of PRRA (The Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration), involving 8000 small farms, will develop into a hot political issue,” a week later, Dorvillier exclaims that “If you think industrial development has been impressive in the last few years, you haven’t seen anything yet!”[4] The News Letter is ultimately presented through a capitalist lens that views economic growth and industrialization as the primary markers for economic success, which Puerto Rico was achieving throughout the 1950s and 1960s. While industry did undoubtedly grow, some fears of instability remained. The growing concerns are seen throughout the progression of the newsletter’s narrative:

“Shortage of workers to harvest the new crop expected.” (Nov. 14, 1953)

“Shortage of workers to harvest the new crop expected.” (Nov. 14, 1953)- “The sugar industry is sick. Its condition is serious, but not yet critical (Nov. 21, 1953)

- “Cost of living continues to rise” (Various issues between 1954 and 1959)

The duality between economic growth and anxieties is no better presented than in Governor Luis Muñoz Marín’s 1958 annual address at the “State of the Commonwealth.” Muñoz Marín explains that while capital investments are up, attracting new industries is becoming increasingly complex. Similarly, per capita income is increasing, but it comes with a warning that a labor shortage will occur if specific demands are unmet. While manufacturing income was up 15%, agriculture was down by 7%. While wages are acknowledged, Muñoz Marín directs workers not to rely on government-set wages but to instead bargain for their wages. The signs of economic prosperity with an underlying forewarning are a trend that defines The Dorvillier.

Washington Pipeline

The “Washington Pipeline” is a section included in the issues found in the first two volumes (1953-1955). The pipeline focuses on insider knowledge of political developments, and it is one that I see as the most unique and essential to developing the identity of the newsletter in its early years. It is unclear who provided the newsletter with the information in the pipeline. Still, it gives us insight into which policies and conversations were significant for the “businessman.” This section is central in propagating themes of industrial development, concerns surrounding the impact of migration on Puerto Rico and the US mainland, labor demands and instability, and a variety of other issues, like the debate on statehood.

The “Washington Pipeline” is a section included in the issues found in the first two volumes (1953-1955). The pipeline focuses on insider knowledge of political developments, and it is one that I see as the most unique and essential to developing the identity of the newsletter in its early years. It is unclear who provided the newsletter with the information in the pipeline. Still, it gives us insight into which policies and conversations were significant for the “businessman.” This section is central in propagating themes of industrial development, concerns surrounding the impact of migration on Puerto Rico and the US mainland, labor demands and instability, and a variety of other issues, like the debate on statehood.

In the November 7th, 1953, issue, the Newsletter brings attention to the qualms brought forth by then Democrat Senator (MA) and future US President, John F. Kennedy. Sen. Kennedy brings attention to what he sees as a potential drain on industry in Massachusetts due to the luring of Puerto Rico’s cheaper labor. The counterargument presented by The Dorvillier is that the industry is moving south rather than to Puerto Rico, but the politicization of Puerto Rico’s industry is a point of interest. The Dorvillier rehashes this topic multiple times and clarifies that Puerto Rico should not be seen as the source of New England’s labor drainage. This rhetoric may be indicative of the broader trend of anti-Puerto Rican sentiments that were growing throughout the United States, referred to as the “Puerto Rican problem”.[5]

In the November 7th, 1953, issue, the Newsletter brings attention to the qualms brought forth by then Democrat Senator (MA) and future US President, John F. Kennedy. Sen. Kennedy brings attention to what he sees as a potential drain on industry in Massachusetts due to the luring of Puerto Rico’s cheaper labor. The counterargument presented by The Dorvillier is that the industry is moving south rather than to Puerto Rico, but the politicization of Puerto Rico’s industry is a point of interest. The Dorvillier rehashes this topic multiple times and clarifies that Puerto Rico should not be seen as the source of New England’s labor drainage. This rhetoric may be indicative of the broader trend of anti-Puerto Rican sentiments that were growing throughout the United States, referred to as the “Puerto Rican problem”.[5]

Questions surrounding Puerto Rico’s status are also a point of interest in the Pipeline. The “independence questions” are acknowledged throughout 1953 as the conversations of Hawaiian statehood began to gain steam. Fears of independence talk seem to be a prominent concern and are tied to anti-communist sentiments. Still, by 1954, independence was waved away as an improbable fringe position often accompanied by radicalism.

Questions surrounding Puerto Rico’s status are also a point of interest in the Pipeline. The “independence questions” are acknowledged throughout 1953 as the conversations of Hawaiian statehood began to gain steam. Fears of independence talk seem to be a prominent concern and are tied to anti-communist sentiments. Still, by 1954, independence was waved away as an improbable fringe position often accompanied by radicalism.

The Dorvillier News Letter never addresses why it discontinued the Pipeline. The most reasonable assumption is that they receive more information as they grow in relevance, which makes it difficult to condense it into a paragraph or two. Although not easily noticeable, after 1954, the formatting of the issues did strip away the majority of the narrative style and focused on more densely packing the newsletter with a broader scope of datasets and political information. With that said, migration and status remained in the Dorvillier after the removal of the Pipeline. While migration tapers off in 1958 due to the economic recession, status reignites after Hawaii was given statehood in 1959.

The Dorvillier News Letter never addresses why it discontinued the Pipeline. The most reasonable assumption is that they receive more information as they grow in relevance, which makes it difficult to condense it into a paragraph or two. Although not easily noticeable, after 1954, the formatting of the issues did strip away the majority of the narrative style and focused on more densely packing the newsletter with a broader scope of datasets and political information. With that said, migration and status remained in the Dorvillier after the removal of the Pipeline. While migration tapers off in 1958 due to the economic recession, status reignites after Hawaii was given statehood in 1959.

A Little Something on Migration

Because of my research and interest, I would like to touch on migration briefly. The Dorvillier News Letter pays significant attention to migration and even alludes to circular migration. The analysis of migration data is often tied to concerns of unemployment opportunities in Puerto Rico and labor demands in the United States.

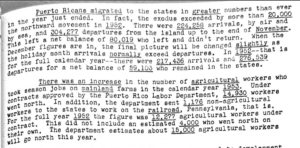

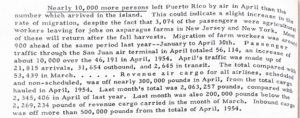

The most consistent review of data done by The Dorvillier is air traffic. Every volume from 1953 to 1959 includes a review of the number of departures and arrivals to Puerto Rico. Although the data does not necessarily indicate how many Puerto Ricans left without returning, they use it as an indicator, along with other data, as to whether migration is increasing or decreasing. Below are a few examples of this practice:

The number of Puerto Ricans migrating to the United States is presented as a gauge of economic health in the United States and Puerto Rico. Those who are leaving are doing so because of job opportunities in the United States, in turn allowing the economy in Puerto Rico to industrialize without the burden of an unemployed mass of workers. However, hotels and sugar plantations are having difficulties in finding laborers and maintaining them. On the other hand, those who migrate away send millions of dollars back to their families in Puerto Rico. As you can tell, this was a very complex and difficult issue to solve for the Puerto Rican government, which is attempting to prioritize industry.

As migration ebbs and flows throughout the 1950s, the Dorvillier brings attention to the ongoing pushback by political leaders who see the migration as a “Puerto Rican problem,” as briefly mentioned above. This was seen as enough of an issue to draw attention from the United States Joint Committee on Immigration and Nationality Policy.[6] After the pushback, the Dorvillier continues to touch on migration, but by 1958 it is reported to have significantly slowed to a “standstill.” Part of employing the labor force is done through government programs that incentivize Puerto Ricans to go to the mainland. The Dorvillier explains that the scarcity of opportunities and the inability to relocate Puerto Rican workers are real concerns for investors. By 1950, there is a bounce back in migration, but the Dorvillier Newsletter cuts down significantly on its reporting throughout the year, and the value of what it had already reported remains.

As migration ebbs and flows throughout the 1950s, the Dorvillier brings attention to the ongoing pushback by political leaders who see the migration as a “Puerto Rican problem,” as briefly mentioned above. This was seen as enough of an issue to draw attention from the United States Joint Committee on Immigration and Nationality Policy.[6] After the pushback, the Dorvillier continues to touch on migration, but by 1958 it is reported to have significantly slowed to a “standstill.” Part of employing the labor force is done through government programs that incentivize Puerto Ricans to go to the mainland. The Dorvillier explains that the scarcity of opportunities and the inability to relocate Puerto Rican workers are real concerns for investors. By 1950, there is a bounce back in migration, but the Dorvillier Newsletter cuts down significantly on its reporting throughout the year, and the value of what it had already reported remains.

Conclusion:

At the core of The Dorvillier is the duality that has become ingrained in the conversation surrounding the ELA: increased industry, robust market growth, rapid industrialization, and an increase in living conditions; while also fostering a dependency on U.S. investors and markets, an inability to transition its workforce fast enough from the agrarian to industrial sectors, and early signs of shortcomings that are minimized by the promises of investment and development that are coming from U.S. investments. The Dorvillier brings attention to the wide array of investments that are being pumped into Puerto Rico throughout the 1950s. There is no doubt that Puerto Rico was in a period of industrial boom and the production of wealth was heavily central for the Dorvillier in developing their version of a Puerto Rican narrative, but if you read between the lines, you will see drops of information on the increasing concerns of labor, questions on the status of the island, the importance of migration, and so on.

What The Dorvillier does best beyond the numbers may be in the insight that it gives on the development of dialogue. As economic and political issues progress, the conversations shift in real time. The uniqueness in these sources that differentiate them from other newspapers or newsletters is that we see the continuity within the analysis because William Dorvillier was, as far as I can tell, the primary contributor to these articles. In a way, it functions as both a news source and a sort of inward conversation, a view of what was thought to be the most important issues for businessmen. What we get is an idea of the shifting landscape of Puerto Rican politics, economics, and, to some degree, everyday life during this period.

References

Dorvillier, William J. The Dorvilier News Letter, Vol. 1-6, 1953-1959, Biblioteca y Hemeroteca Puertorriqueña (UPPRP).

Suarez, Nydia R. “The Rise and Decline of Puerto Rico’s Sugar Economy” Economic Research Service/USDA. 1998.

Notes

[1] Marvine How. “W.J. Dorvillier, 85; Founded Newspaper and Won a Pulitzer.” 1993. May 6, 1993; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times, D22.

[2] There is a typographical error in the article. The name of the company is not Western Electric. The correct name is Weston Electric.

[3] A review of Puerto Rico’s sugar decline was published by the USDA in 1998. It marked 1952 as the year of highest sugar production in Puerto Rico at 12.5 million tons. The investments and policies passed throughout the 1950s that benefited industrialization did not translate to the agricultural sector. This in turn squeezed the sugar industry which saw a stark decline of production within the following decade and by the 1990s was functionally extinct.

[4] William J. Dorvillier, The Dorvilier News Letter, Vol. 1, November 7, 1953, Biblioteca y Hemeroteca Puertorriqueña (UPPRP).

[5] The “Puerto Rican Problem” is defined by the growing anti-immigration sentiments against Puerto Ricans. The perception of Puerto Ricans as foreign migrants rather than Americans is believed to have proliferated through media campaigns which demonized and othered Puerto Ricans as impoverished and lacking perceived American characteristic. While the Dorvillier references the “Problem” a bit more loosely, Edgardo Meléndez spends time on developing the Problem in his book The “Puerto Rican Problem” in Postwar New York City.

[6] The committee is a product of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952.